How Acacia Fiber Supports Digestive Health Without Bloating or Gas

Gut health is important, but not all prebiotics work the same way. People with sensitive stomachs often struggle to find solutions that don't make them feel worse. Acacia fiber, also called gum arabic, is a gentle but powerful ingredient that helps gut health without causing the uncomfortable side effects that other prebiotics often do.[1]

This is why we formulated MicroBiome Restore™ without microcrystalline cellulose and other problematic fillers—using acacia and other gentle prebiotics instead.

| Key Takeaways: Acacia Fiber Benefits | |

|---|---|

| Gentle Prebiotic | Ferments slowly throughout the digestive tract, minimizing gas, bloating, and discomfort |

| Gut Barrier Support | Promotes production of butyrate and mucin to strengthen intestinal lining and protect against leaky gut—learn more about butyrate and short-chain fatty acid benefits in our complete guide |

| Anti-Inflammatory | Reduces pro-inflammatory markers in the gut while promoting anti-inflammatory responses |

| SCFA Production | Supports the creation of beneficial short-chain fatty acids that nourish colon cells |

| Low FODMAP Compatible | Well-tolerated even by those with IBS and other inflammatory bowel conditions |

| Synergistic Effect | Works harmoniously with probiotics to enhance their colonization and effectiveness |

At BioPhysics Essentials, we've included acacia as a key ingredient in our MicroBiome Restore™ formula because of its unique benefits for sensitive digestive systems. Let's explore why acacia deserves recognition as a gut health powerhouse.

What Makes Acacia Special for Sensitive Guts?

Acacia fiber is different from other prebiotics because it ferments slowly in the gut.[2] Many common prebiotics like inulin or fructooligosaccharides (FOS) ferment quickly, often causing gas, bloating, and stomach pain. This makes them hard to use for people with sensitive stomachs or IBS. The rapid fermentation of these fibers can lead to a sudden surge in gas production within the first few hours of consumption, which explains why many people experience immediate discomfort after taking typical prebiotic supplements. While inulin has its own benefits, its rapid fermentation makes it unsuitable for many people with digestive sensitivities.

Acacia's gentle nature comes from its unique arabinogalactan structure—a complex branched polysaccharide consisting primarily of arabinose and galactose sugars.[3] This molecular architecture allows it to be broken down gradually throughout the entire digestive tract rather than being rapidly consumed in the proximal colon. This slow fermentation means you get all the benefits of a prebiotic without the uncomfortable side effects. It's really helpful for people who've had bad experiences with other fiber supplements or prebiotics before.

Acacia fiber's gentle prebiotic properties make it especially relevant during the postpartum period, when it can help sustain the Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium populations that support breast milk quality during breastfeeding.

Unlike fast-fermenting prebiotics that can overwhelm your digestive system, acacia's structure allows for a controlled, steady breakdown. This gradual fermentation spreads the prebiotic activity evenly from the small intestine through the colon, preventing the sudden bacterial growth that usually causes discomfort. Studies show that acacia fiber produces much less gas than other prebiotic fibers, making it perfect for people with sensitive guts or digestive disorders.[4] In fact, clinical studies have demonstrated that doses of up to 40 grams per day of acacia fiber are well-tolerated without significant increases in gastrointestinal discomfort—a stark contrast to other prebiotics that can cause symptoms at doses as low as 5-10 grams daily.[30]

Understanding Acacia Fiber's Composition and Origin

Acacia fiber, also known as gum arabic or acacia gum, is derived from the dried sap of Acacia senegal and Acacia seyal trees, which are primarily found in Sudan, Chad, and Nigeria.[31] These trees have been harvested sustainably for thousands of years, making acacia one of the oldest known natural gums with documented use dating back over 5,000 years in traditional medicine and food preparation.

The harvesting process involves making incisions in the bark of acacia trees, allowing the sap to exude and harden into translucent nodules. These nodules are then collected, cleaned, and processed into a fine powder that can be easily incorporated into foods, beverages, and dietary supplements. The acacia gum used in supplements typically contains 85-90% soluble dietary fiber, making it one of the most fiber-dense natural ingredients available.[32]

What makes acacia particularly valuable is its remarkably low viscosity compared to other soluble fibers. Even at concentrations of 30-50%, acacia solutions remain fluid and easy to mix, whereas many other fiber supplements thicken dramatically and become difficult to consume. This property allows acacia to be used at therapeutic doses without affecting the texture or palatability of foods and beverages—a significant advantage for people who struggle with the thick, gel-like consistency of other fiber supplements.

How Acacia Supports Your Gut Microbiome

Acacia fiber works as a prebiotic by feeding the good bacteria in your gut, especially Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species.[5] Learn more about the specific benefits of Bifidobacterium lactis and why supporting these strains matters for digestive health. These good bacteria play important roles in keeping your digestion healthy and supporting your immune system. The prebiotic effect of acacia has been well-documented across multiple clinical studies, consistently showing increases in beneficial bacterial populations within just a few weeks of supplementation.

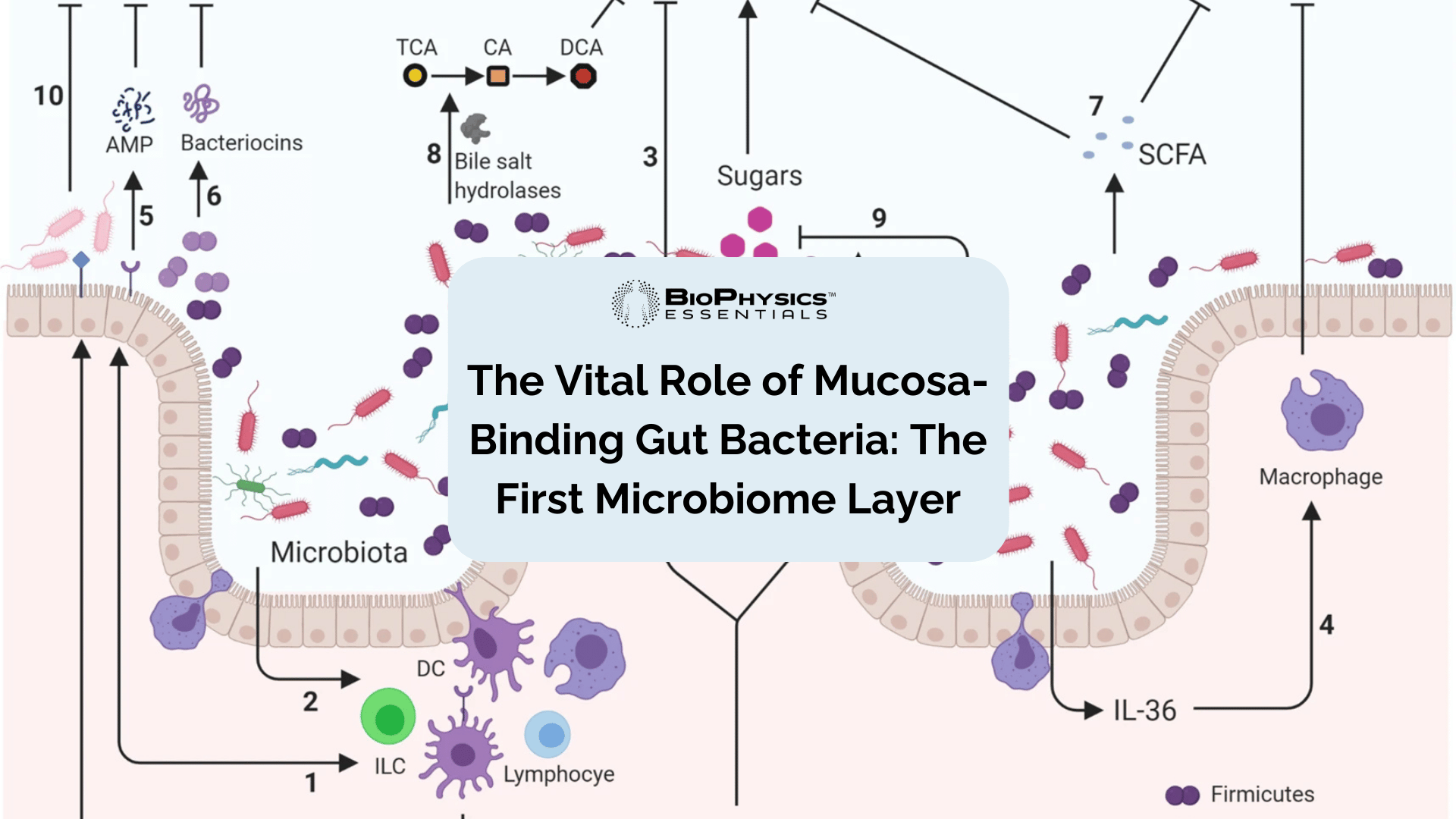

When these good bacteria break down acacia fiber, they make short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which is the main energy source for the cells lining your colon.[6] Butyrate helps strengthen your gut barrier, reduce inflammation, and create an environment where good bacteria can grow while bad bacteria are kept in check.[7] This process of bacterial fermentation is fundamental to gut health, as it transforms indigestible fiber into bioactive compounds that have far-reaching effects throughout the body.

Research shows that acacia fiber can increase good bacteria populations in just four weeks of regular use.[8] In one controlled study, supplementation with 10 grams of acacia fiber daily led to significant increases in both Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus counts, with effects comparable to or exceeding those seen with the same dose of inulin—but without the gastrointestinal side effects.[33] This selective feeding is important for maintaining bacterial diversity, which is a sign of a healthy gut. If you're experiencing symptoms of bacterial imbalance, our guide on Lactobacillus deficiency signs and symptoms can help you identify what's happening in your gut.

A diverse microbiome better protects against harmful bacteria and provides more complete metabolic functions. The gut microbiome performs thousands of different metabolic reactions, producing vitamins, neurotransmitters, and other compounds essential for health. When we support microbial diversity through prebiotic fibers like acacia, we're essentially supporting all of these downstream functions. Acacia also helps create the right pH in your colon that further stops bad microorganisms from growing while encouraging good ones to thrive.[9] The production of SCFAs naturally lowers the pH of the colon, creating an acidic environment that most pathogenic bacteria cannot tolerate.

Beyond simply increasing beneficial bacteria, acacia fiber has been shown to actively inhibit pathogenic species. Research using in vitro colon models has demonstrated that acacia supplementation significantly reduces populations of Clostridium histolyticum, a bacterial group commonly associated with gut dysbiosis and implicated in inflammatory bowel conditions.[34] This dual action—promoting beneficial bacteria while suppressing harmful ones—makes acacia particularly valuable for people working to restore balance to their gut microbiome after antibiotic use or during recovery from digestive illness.

- Gentle prebiotic that doesn't cause bloating or gas

- Promotes growth of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium

- Supports production of gut-healing short-chain fatty acids

- Helps strengthen the gut barrier function

- Provides anti-inflammatory benefits

- Supports regular bowel movements without urgency

- Well-tolerated by sensitive digestive systems

Acacia for Gut Barrier Support

The gut barrier is your body's first defense against harmful substances. When this barrier becomes damaged—often called "leaky gut"—it can cause many health problems including stomach pain, food sensitivities, and inflammation throughout your body.[10] For a deeper exploration of this topic, see our complete guide on probiotics for intestinal barrier repair. The intestinal barrier must maintain a delicate balance: it needs to be selectively permeable to allow nutrients to pass through while blocking toxins, pathogens, and undigested food particles from entering the bloodstream.

Acacia fiber helps support and strengthen this important barrier in several ways. It promotes the production of butyrate, which feeds the cells lining your gut wall and serves as their primary energy source.[11] Colonocytes (the cells lining the colon) derive up to 70% of their energy from butyrate, making SCFA production absolutely critical for maintaining barrier integrity. It also stimulates the production of mucin, which is part of the protective mucus layer that lines your digestive tract. Acacia also helps balance inflammation in the gut, which is essential for maintaining a healthy gut lining.

Your intestinal barrier is made of a single layer of epithelial cells connected by tight junctions—protein structures that control what passes through your intestinal wall.[12] These tight junctions act as selective gatekeepers, allowing small molecules like water, electrolytes, and digested nutrients to pass while blocking larger molecules and pathogens. The integrity of these junctions is maintained by specialized proteins including occludin, claudins, and zonula occludens (ZO) proteins.

Research shows that dietary fibers help increase the expression of genes that make these tight junction proteins, especially claudin and occludin, which are essential for keeping the barrier strong.[13] When tight junction integrity is compromised, the spaces between cells widen, allowing substances that should remain in the intestinal lumen to pass into the bloodstream—a condition known as increased intestinal permeability or "leaky gut." This can trigger systemic inflammation and immune reactions that affect organs far beyond the digestive system.

The mucin production stimulated by acacia creates a thicker protective mucus layer that acts as a physical barrier against harmful substances.[14] The intestinal mucus layer is actually organized into two distinct zones: a dense inner layer that remains sterile and firmly attached to the epithelium, and a looser outer layer where commensal bacteria reside. This mucus barrier contains antimicrobial peptides and secretory IgA that provide additional protection. When the mucus layer becomes thin or compromised, bacteria can come into direct contact with intestinal cells, triggering inflammatory responses.

This mucus layer is particularly important for people with inflammatory conditions like IBD, where the mucus layer often gets thin. By supporting both the cell connections and the protective mucus layer, acacia provides complete support for maintaining a strong intestinal barrier. Studies in animal models have shown that fiber-deficient diets lead to degradation of the mucus barrier, while adequate fiber intake—particularly from sources like acacia—helps maintain optimal mucus thickness and quality.[35]

Acacia for Inflammatory Bowel Conditions and IBS

For people with inflammatory bowel conditions like Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), finding supplements that don't make symptoms worse can be hard. Acacia fiber offers a gentle approach that can provide prebiotic benefits without worsening symptoms.[15] Many people with these conditions have tried increasing their fiber intake only to experience severe flare-ups, leading them to avoid fiber altogether—which unfortunately can worsen their condition in the long term. If bloating is your primary concern, our guide on clinically proven probiotic strains for bloating relief covers which specific bacteria help most.

Research has shown that acacia fiber helps reduce inflammatory markers in the gut while promoting anti-inflammatory responses.[16] Unlike many prebiotics that are FODMAPs (which can trigger symptoms in IBS patients), acacia fiber is usually well-tolerated even by those following low FODMAP diets.[17] FODMAPs—Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols—are short-chain carbohydrates that are rapidly fermented by gut bacteria, producing gas and drawing water into the intestines. This can cause severe symptoms in people with IBS, including bloating, cramping, diarrhea, and pain.

Its gradual fermentation minimizes gas production and bloating, making it less likely to cause pain or discomfort in sensitive intestines. The low FODMAP nature of acacia has been confirmed by Monash University, the leading research institution on the FODMAP diet, and several acacia fiber products have received FODMAP-friendly certification.[36]

A recent randomized controlled trial involving 180 IBS patients with constipation found that daily supplementation with 10 grams of acacia fiber for 4 weeks significantly improved stool frequency compared to placebo (P < 0.001), with a trend toward decreased constipation symptoms.[18] Importantly, the study also found that acacia supplementation did not trigger higher severity scores or worsen IBS symptoms, demonstrating its excellent tolerance even in this highly sensitive population. Many participants reported feeling more comfortable and experiencing less abdominal pain during the intervention period.

Studies of acacia fiber have found reductions in key inflammatory markers, including TNF-α, IL-6, and CRP.[19] In a Phase II clinical trial involving patients with rheumatoid arthritis—another inflammatory condition—30 grams daily of acacia fiber for 12 weeks resulted in significant decreases in TNF-α levels. These inflammatory markers are usually high during active disease phases and are targets for many medications. Acacia fiber also appears to increase the production of anti-inflammatory compounds like IL-10, which helps regulate immune responses in the gut.[20]

The anti-inflammatory effects of acacia appear to work through multiple mechanisms. First, the SCFAs produced during fermentation—particularly butyrate—directly inhibit the activation of NF-κB, a key inflammatory signaling pathway.[37] Second, the improved gut barrier function reduces bacterial translocation and subsequent systemic inflammation. Third, acacia may have direct immunomodulatory effects independent of fermentation, as suggested by studies showing improvements in immune markers even in subjects with low baseline bacterial fermentation capacity.

For people with IBS specifically, the combination of low FODMAP compatibility, gentle fermentation profile, and anti-inflammatory properties makes acacia an ideal fiber choice. Unlike psyllium husk, which can cause cramping in some IBS patients, or inulin, which is high FODMAP and often triggers symptoms, acacia provides the benefits of fiber supplementation without the drawbacks. The dual action of providing gentle fiber while also reducing inflammation makes acacia especially valuable for those managing chronic inflammatory gut conditions.

The Low FODMAP Advantage

The low FODMAP diet has become one of the most evidence-based dietary interventions for managing IBS symptoms, with research showing symptom improvement in 50-80% of IBS patients who follow the diet correctly.[38] However, one of the major challenges with the low FODMAP diet is getting adequate fiber intake, as many high-fiber foods are also high in FODMAPs.

This is where acacia fiber becomes particularly valuable. Because acacia is low FODMAP, it can be used during all phases of the FODMAP diet, including the strict elimination phase. This allows people with IBS to maintain adequate fiber intake—which is crucial for maintaining healthy gut bacteria and regular bowel movements—without triggering the rapid fermentation and gas production that comes from high FODMAP fibers.

The molecular structure of acacia sets it apart from FODMAP fibers. While inulin and FOS are composed of short fructose chains that are rapidly fermented in the proximal colon, acacia's complex arabinogalactan structure requires specialized enzymes to break down. This means fermentation occurs slowly and throughout the length of the colon, rather than all at once in the first section. The result is steady, manageable SCFA production without the sudden gas release that causes bloating and discomfort.[39]

Clinical evidence supports the use of acacia for IBS patients following low FODMAP diets. Multiple studies have shown that acacia supplementation improves bowel habits, reduces abdominal pain, and enhances quality of life in IBS patients without increasing symptom severity scores.[40] This makes acacia one of the few prebiotics that can truly be called "IBS-friendly." For practical guidance on maximizing your results, see our research on the best time to take probiotics according to science.

The Synergistic Effect: Acacia + Probiotics

While acacia fiber alone offers great benefits for gut health, its power gets even stronger when combined with good probiotics. This combination creates what scientists call a "synbiotic" effect—where the combination works better than either one alone.[21] The concept of synbiotics is based on the understanding that probiotics need proper nutrition to survive, colonize, and thrive in the digestive tract. Without adequate prebiotic fuel, many probiotic strains simply pass through the digestive system without establishing residence or providing lasting benefits.

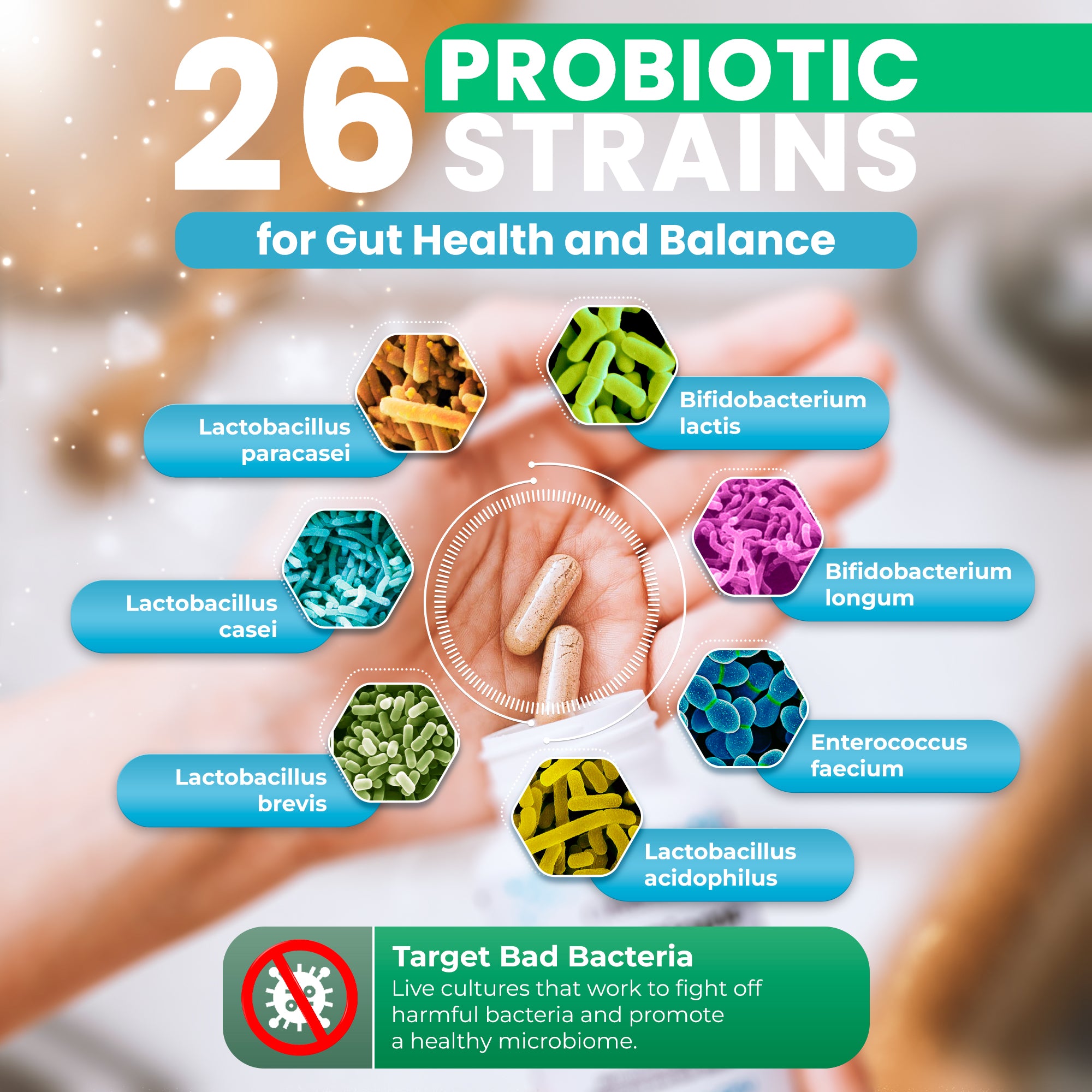

In our MicroBiome Restore™ formula, we've carefully balanced acacia fiber with 26 probiotic strains to maximize this teamwork. The acacia fiber feeds beneficial bacteria, particularly Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species, which are well-represented in our probiotic blend.[22] This selective feeding helps these good bacteria thrive and establish colonies in your gut. The diverse strain selection ensures that we're supporting multiple beneficial species, each with unique functions in maintaining digestive health, immune function, and metabolic balance. Our guide on single-strain vs. multi-strain probiotics explains why this diversity matters for comprehensive gut support.

The synbiotic approach solves a common problem in probiotic supplements—making sure that beneficial bacteria not only survive the journey through your digestive system but also successfully establish themselves in your gut. Research shows that probiotic strains paired with their preferred prebiotic food source show much higher rates of colonization and staying power.[23] In fact, studies comparing probiotics alone versus probiotics with prebiotics have found that the synbiotic combinations result in bacterial counts 10-100 times higher in the colon, along with greater improvements in clinical outcomes.

In our MicroBiome Restore™ formula, acacia serves as an ideal companion to the probiotic strains, creating good conditions for their growth while also inhibiting harmful bacteria. This relationship goes beyond simple colonization support—the substances produced through this interaction have been shown to have broader health benefits, including enhanced immune function and improved gut barrier function. The carefully balanced ratio of acacia to probiotic strains in our formula is designed to optimize this synergistic relationship, providing complete support for establishing and maintaining a healthy gut microbiome.

One particularly interesting aspect of the acacia-probiotic synergy is its effect on probiotic viability during storage and digestion. Studies have shown that acacia can act as a protective matrix for probiotic bacteria, improving their survival rates during both manufacturing processes like freeze-drying and during their transit through the acidic stomach environment.[41] This means that not only does acacia feed probiotics once they reach the colon, but it may also help more of them survive to get there in the first place.

Acacia and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production

One of the most important benefits of acacia fiber is its ability to support the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the gut. When good bacteria ferment acacia fiber, they produce these valuable compounds, particularly butyrate, acetate, and propionate.[24] SCFAs represent one of the primary mechanisms through which gut bacteria influence host health, serving as signaling molecules, energy sources, and regulators of immune function.

Butyrate is especially important as it serves as the main energy source for the cells lining your colon.[25] Colonocytes preferentially utilize butyrate for energy through beta-oxidation, and approximately 70% of the energy needed by these cells comes from butyrate metabolism. It helps strengthen the gut barrier, reduce inflammation, and may even help prevent colorectal cancer. Research has shown that butyrate induces apoptosis (programmed cell death) in cancerous colon cells while promoting the health of normal cells—a selective effect that makes it particularly valuable for colon health.[42]

Acetate and propionate support metabolic health, help regulate appetite, and provide energy for various tissues in your body.[26] Acetate, the most abundant SCFA in the colon, can cross into systemic circulation and reach peripheral tissues, where it influences lipid metabolism and energy expenditure. Propionate travels to the liver via the portal vein, where it regulates gluconeogenesis and cholesterol synthesis. Both acetate and propionate activate G-protein coupled receptors (GPR41 and GPR43) that influence metabolic processes, immune responses, and even appetite regulation through effects on hormone secretion.

The balanced production of these SCFAs through acacia fermentation offers significant advantages for sensitive digestive systems. The relationship between acacia fiber and SCFA production is particularly noteworthy because of its balanced profile. While many prebiotics favor the production of just one or two SCFAs, acacia fermentation yields a more complete spectrum.[27] This balanced SCFA profile provides more complete support for gut health, as each SCFA has distinct and complementary effects on intestinal and systemic physiology.

Research indicates that butyrate production from acacia fermentation can increase significantly compared to baseline levels, providing substantial nourishment for colon cells. Beyond their local effects in the gut, these SCFAs have whole-body benefits—acetate travels to the liver where it influences fat metabolism, while propionate affects blood sugar regulation and satiety signaling.[28] Some studies have shown that propionate supplementation can reduce food intake and prevent weight gain in humans, likely through effects on appetite-regulating hormones like peptide YY and GLP-1.

Furthermore, SCFAs act as signaling molecules that interact with receptors throughout the body, influencing immune function, hormone regulation, and even brain processes. The gut-brain axis, which represents bidirectional communication between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system, is significantly influenced by SCFAs. Research suggests that SCFAs can cross the blood-brain barrier and influence neurotransmitter production, potentially affecting mood, cognition, and behavior.[43] Our article on the gut-brain axis and mental well-being explores this fascinating connection in depth. This wide-ranging impact explains why acacia's SCFA-promoting effects extend well beyond digestive comfort to influence overall health and wellbeing.

fermentation yields a more complete spectrum.[27] Beyond their local effects in the gut, these SCFAs have whole-body benefits—acetate travels to the liver where it influences fat metabolism, while propionate affects blood sugar regulation and feeling full after eating.[28] Furthermore, SCFAs act as signaling molecules that interact with receptors throughout the body, influencing immune function, hormone regulation, and even brain processes.

How to Incorporate Acacia into Your Gut Health Regimen

Adding acacia fiber to your gut health routine can make a big difference, especially if you have a sensitive digestive system. The easiest way to benefit from acacia is through our MicroBiome Restore™ formula, which includes acacia fiber as one of its 9 organic prebiotics, working alongside 26 live probiotic strains. Unlike supplements packed with flow agents and fillers, every ingredient in MicroBiome Restore™ serves a functional purpose.

For complete gut support, consider our Gut Essentials Protocol, which combines MicroBiome Restore™ with X-Cellerator™ Full Spectrum Minerals. This two-part approach addresses both the microbial balance and the structural integrity of your gut lining. The minerals in X-Cellerator™ are particularly important for gut health, as magnesium, zinc, and other trace minerals play critical roles in maintaining tight junction integrity and supporting the enzymatic processes involved in digestion and nutrient absorption.

Most published studies report a daily dose of acacia fiber between 5-30 grams used for up to 3 months with no safety or tolerability concerns.[29] Clinical trials have demonstrated that acacia is well-tolerated even at doses of 40 grams per day, which is remarkable compared to other prebiotics that cause discomfort at much lower doses. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recognized acacia gum as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) since the 1970s, and more recently confirmed its status as dietary fiber for nutrition labeling purposes.[44]

When starting any fiber supplement, including those containing acacia, it's best to begin with a lower dose and gradually increase over several days to weeks. This allows your gut microbiome to adapt to the increased fiber intake and minimizes any temporary digestive adjustment. While acacia is gentler than most fibers, giving your system time to adjust ensures the most comfortable experience. Start with about one-third to one-half of the target dose for the first week, then gradually increase as tolerated.

Remember to drink plenty of water when taking prebiotic supplements, as water helps support optimal fermentation and prevents constipation. Adequate hydration is essential for fiber to work properly—fiber absorbs water in the digestive tract, which helps create bulk and promotes healthy bowel movements. Aim for at least 8-10 glasses of water daily when supplementing with any type of fiber.

For best results, take your acacia-containing supplement consistently at the same time each day. Many people find that taking it with meals helps with both compliance and tolerability. The prebiotics in MicroBiome Restore™ work synergistically with the probiotics, so taking them together ensures that the beneficial bacteria have immediate access to their preferred food source. This consistency helps establish a stable, healthy gut microbiome over time.

Acacia Fiber and Digestive Regularity

One of the most immediately noticeable benefits of acacia fiber supplementation is its effect on digestive regularity. Unlike stimulant laxatives that force bowel movements through irritation, acacia works naturally to promote regular, comfortable bowel function.[45] The mechanism is multifaceted: acacia increases stool bulk through water retention, improves stool consistency through fermentation byproducts, and enhances intestinal motility through SCFA production.

For people with constipation-predominant IBS (IBS-C), acacia has shown particular promise. The clinical trial mentioned earlier demonstrated that acacia supplementation significantly increased stool frequency without causing urgency or diarrhea—a delicate balance that's hard to achieve with many fiber supplements.[46] Participants reported softer, more comfortable bowel movements without the cramping or urgency that sometimes accompanies other constipation remedies.

Interestingly, acacia may also help with diarrhea-predominant conditions. The soluble fiber helps absorb excess water in the intestinal tract while the mucilage properties of acacia can help soothe inflamed intestinal tissue. This bidirectional effect—helping both constipation and diarrhea—makes acacia particularly valuable for people with IBS-M (mixed type) who alternate between both extremes. The key is acacia's ability to normalize stool consistency rather than pushing bowel function in one direction or another.

Acacia fiber selectively feeds beneficial bacteria including Lactobacillus rhamnosus, one of the most extensively studied strains for digestive health and antibiotic-associated diarrhea prevention.

Clinical studies have also shown improvements in other markers of digestive comfort beyond just bowel frequency. Many participants report reductions in bloating, abdominal pain, and flatulence after several weeks of acacia supplementation. These improvements typically become noticeable within 2-4 weeks of consistent use, though some people experience benefits sooner.

Conclusion: Why Acacia Deserves Recognition

Acacia fiber truly is an unsung hero for gut health, particularly for those with sensitive digestive systems. Its gentle yet effective nature makes it stand out among prebiotics, providing all the benefits without the uncomfortable side effects often associated with other fiber supplements.

By incorporating acacia fiber through our scientifically formulated MicroBiome Restore™ and Gut Essentials Protocol, you can harness the power of this remarkable prebiotic for your sensitive gut. Whether you're dealing with digestive discomfort, working to restore gut health after antibiotics, or simply looking to support your overall wellbeing, acacia fiber offers a gentle approach to achieving a balanced, healthy gut microbiome. To learn more about how prebiotics and probiotics work together, explore our guide on the top benefits of combining prebiotics and probiotics.

Visit our probiotics collection to learn more about how our acacia-containing formulas can help support your journey to optimal gut health.

References

- Al-Jubori, S. S., Al-Naqeeb, G., Atmani, A. M., Tanner, B. J., & Al-Qaisi, T. S. (2023). Acacia senegal and Acacia seyal: Comprehensive review on chemistry, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. Phytotherapy Research, 37(2), 456-482.

- Terpend, K., Possemiers, S., Daguet, D., & Marzorati, M. (2013). Arabinogalactan and fructo-oligosaccharides have a different fermentation profile in the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME®). Environmental Microbiology Reports, 5(4), 595-603.

- Cherbut, C., Michel, C., Raison, V., Kravtchenko, T., & Severine, M. (2003). Acacia gum is a bifidogenic dietary fibre with high digestive tolerance in healthy humans. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, 15(1), 43-50.

- Calame, W., Weseler, A. R., Viebke, C., Flynn, C., & Siemensma, A. D. (2008). Gum arabic establishes prebiotic functionality in healthy human volunteers in a dose-dependent manner. British Journal of Nutrition, 100(6), 1269-1275.

- Rawi, M. H., Abdullah, A., Ismail, A., & Sarbini, S. R. (2021). Manipulation of Gut Microbiota Using Acacia Gum Polysaccharide. ACS Omega, 6(28), 17782-17797.

- Den Besten, G., van Eunen, K., Groen, A. K., Venema, K., Reijngoud, D. J., & Bakker, B. M. (2013). The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. Journal of Lipid Research, 54(9), 2325-2340.

- Chambers, E. S., Preston, T., Frost, G., & Morrison, D. J. (2018). Role of gut microbiota-generated short-chain fatty acids in metabolic and cardiovascular health. Current Nutrition Reports, 7(4), 198-206.

- Min, Y. W., Park, S. U., Jang, Y. S., Kim, Y. H., Rhee, P. L., Ko, S. H., ... & Chang, D. K. (2012). Effect of composite yogurt enriched with acacia fiber and Bifidobacterium lactis. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 18(33), 4563-4569.

- Cherbut, C., Michel, C., Raison, V., Kravtchenko, T., & Meance, S. (2003). Acacia gum is a bifidogenic dietary fibre with high digestive tolerance in healthy humans. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, 15(1), 43-50.

- Kim, Y. S., & Ho, S. B. (2010). Intestinal goblet cells and mucins in health and disease: recent insights and progress. Current Gastroenterology Reports, 12(5), 319-330.

- Suzuki, T., & Hara, H. (2010). Dietary fat and bile juice, but not obesity, are responsible for the increase in small intestinal permeability induced through the suppression of tight junction protein expression in LETO and OLETF rats. Nutrition & Metabolism, 7, 19.

- Anderson, J. M., & Van Itallie, C. M. (2009). Physiology and function of the tight junction. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 1(2), a002584.

- Suzuki, T. (2013). Regulation of intestinal epithelial permeability by tight junctions. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 70(4), 631-659.

- Johansson, M. E., & Hansson, G. C. (2016). Immunological aspects of intestinal mucus and mucins. Nature Reviews Immunology, 16(10), 639-649.

- JanssenDuijghuijsen, L., van den Belt, M., Rijnaarts, I., Vos, P., Guillemet, D., Witteman, B., & de Wit, N. (2024). Acacia fiber or probiotic supplements to relieve gastrointestinal complaints in patients with constipation-predominant IBS: a 4-week randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled intervention trial. European Journal of Nutrition, 63(5), 1983-1994.

- Kamal, E., Kaddam, L. A., Dahawi, M., Osman, M., Salih, M. A., Alagib, A., & Saeed, A. (2018). Gum Arabic fibers decreased inflammatory markers and disease severity score among rheumatoid arthritis patients, Phase II Trial. International Journal of Rheumatology, 2018, 4197537.

- Gibson, P. R., & Shepherd, S. J. (2010). Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 25(2), 252-258.

- JanssenDuijghuijsen, L., van den Belt, M., Rijnaarts, I., Vos, P., Guillemet, D., Witteman, B., & de Wit, N. (2024). Acacia fiber or probiotic supplements to relieve gastrointestinal complaints in patients with constipation-predominant IBS: a 4-week randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled intervention trial. European Journal of Nutrition, 63(5), 1983-1994.

- Kamal, E., Kaddam, L. A., Dahawi, M., Osman, M., Salih, M. A., Alagib, A., & Saeed, A. (2018). Gum Arabic fibers decreased inflammatory markers and disease severity score among rheumatoid arthritis patients, Phase II Trial. International Journal of Rheumatology, 2018, 4197537.

- Ali, B. H., Ziada, A., & Blunden, G. (2009). Biological effects of gum arabic: a review of some recent research. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 47(1), 1-8.

- Pandey, K. R., Naik, S. R., & Vakil, B. V. (2015). Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics- a review. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 52(12), 7577-7587.

- Rawi, M. H., Abdullah, A., Ismail, A., & Sarbini, S. R. (2021). Manipulation of Gut Microbiota Using Acacia Gum Polysaccharide. ACS Omega, 6(28), 17782-17797.

- Kolida, S., & Gibson, G. R. (2011). Synbiotics in health and disease. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 2, 373-393.

- Mortensen, P. B., & Clausen, M. R. (1996). Short-chain fatty acids in the human colon: relation to gastrointestinal health and disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 31(sup216), 132-148.

- Canani, R. B., Costanzo, M. D., Leone, L., Pedata, M., Meli, R., & Calignano, A. (2011). Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 17(12), 1519-1528.

- Koh, A., De Vadder, F., Kovatcheva-Datchary, P., & Bäckhed, F. (2016). From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell, 165(6), 1332-1345.

- Cherbut, C., Michel, C., & Lecannu, G. (2003). The prebiotic characteristics of fructooligosaccharides are necessary for reduction of TNBS-induced colitis in rats. The Journal of Nutrition, 133(1), 21-27.

- Tan, J., McKenzie, C., Potamitis, M., Thorburn, A. N., Mackay, C. R., & Macia, L. (2014). The role of short-chain fatty acids in health and disease. Advances in Immunology, 121, 91-119.

- Al-Jubori, S. S., Al-Naqeeb, G., Atmani, A. M., Tanner, B. J., & Al-Qaisi, T. S. (2023). Acacia senegal and Acacia seyal: Comprehensive review on chemistry, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. Phytotherapy Research, 37(2), 456-482.

- Larson, N., Heiss, C., Schaefer, S., Chohan, M., & Rasmussen, H. (2021). A single dose of acacia gum is well-tolerated and increases the relative abundance of bifidobacteria in healthy adults: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 72(4), 551-561.

- Ashour, A. S., El Aziz, M. M., & Melad, A. S. (2022). A review on saponins from medicinal plants: Chemistry, isolation, and determination. Journal of Nanomedicine Research, 11(1), 282-288.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2021). The Declaration of Certain Isolated or Synthetic Non-Digestible Carbohydrates as Dietary Fiber on Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels: Guidance for Industry. Federal Register.

- Calame, W., Weseler, A. R., Viebke, C., Flynn, C., & Siemensma, A. D. (2008). Gum arabic establishes prebiotic functionality in healthy human volunteers in a dose-dependent manner. British Journal of Nutrition, 100(6), 1269-1275.

- Rawi, M. H., Abdullah, A., Ismail, A., & Sarbini, S. R. (2021). Manipulation of Gut Microbiota Using Acacia Gum Polysaccharide. ACS Omega, 6(28), 17782-17797.

- Desai, M. S., Seekatz, A. M., Koropatkin, N. M., Kamada, N., Hickey, C. A., Wolter, M., ... & Martens, E. C. (2016). A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell, 167(5), 1339-1353.

- Muir, J. G., & Gibson, P. R. (2013). The low FODMAP diet for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome and other gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 9(7), 450-452.

- Segain, J. P., Raingeard de la Blétière, D., Bourreille, A., Leray, V., Gervois, N., Rosales, C., ... & Galmiche, J. P. (2000). Butyrate inhibits inflammatory responses through NFκB inhibition: implications for Crohn's disease. Gut, 47(3), 397-403.

- Halmos, E. P., Power, V. A., Shepherd, S. J., Gibson, P. R., & Muir, J. G. (2014). A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology, 146(1), 67-75.

- Cherbut, C., Michel, C., Raison, V., Kravtchenko, T., & Severine, M. (2003). Acacia gum is a bifidogenic dietary fibre with high digestive tolerance in healthy humans. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, 15(1), 43-50.

- Min, Y. W., Park, S. U., Jang, Y. S., Kim, Y. H., Rhee, P. L., Ko, S. H., ... & Chang, D. K. (2012). Effect of composite yogurt enriched with acacia fiber and Bifidobacterium lactis. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 18(33), 4563-4569.

- Picot, A., & Lacroix, C. (2004). Encapsulation of bifidobacteria in whey protein-based microcapsules and survival in simulated gastrointestinal conditions and in yoghurt. International Dairy Journal, 14(6), 505-515.

- Hamer, H. M., Jonkers, D., Venema, K., Vanhoutvin, S., Troost, F. J., & Brummer, R. J. (2008). Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 27(2), 104-119.

- Silva, Y. P., Bernardi, A., & Frozza, R. L. (2020). The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-brain communication. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 11, 25.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2018). Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Notification for Acacia Gum (Gum Arabic). GRAS Notice No. GRN 000758.

- Eswaran, S., Muir, J., & Chey, W. D. (2013). Fiber and functional gastrointestinal disorders. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 108(5), 718-727.

- JanssenDuijghuijsen, L., van den Belt, M., Rijnaarts, I., Vos, P., Guillemet, D., Witteman, B., & de Wit, N. (2024). Acacia fiber or probiotic supplements to relieve gastrointestinal complaints in patients with constipation-predominant IBS: a 4-week randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled intervention trial. European Journal of Nutrition, 63(5), 1983-1994.

Share and get 15% off!

Simply share this product on one of the following social networks and you will unlock 15% off!